Author: Sharon Simpson, Director of Communications and Stakeholder Engagement

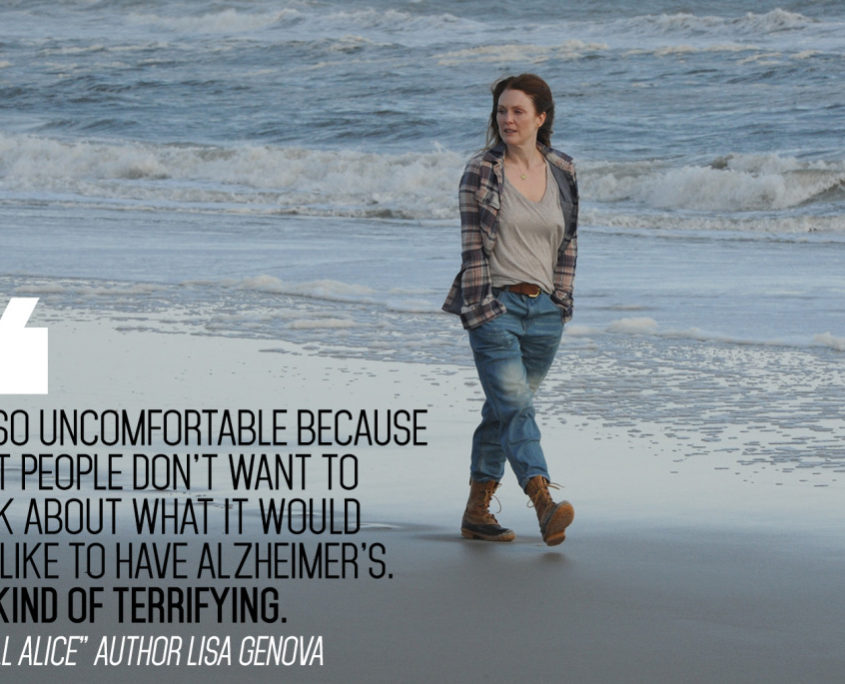

If you are reading this, there is a significant chance that you are living your own version of “Still Alice” and have no need to view another’s journey with Alzheimer’s Disease. For those in the trenches, it may not be of any help or insight to see the progression of this debilitating disease. On the other hand, like me, you may be even more interested than the general public as you seek insight into this disease that is impacting your life. In 2004, 70,000 British Columbians were impacted by Alzheimer’s Disease and this number will grow to more than 110,000 by the end of this year – 2015*.

In the movie, Julianne Moore plays “Alice”, a professor who lives out the Alzheimer’s journey of initial symptoms, diagnosis, shock, tenacity and decline. Based on the book of the same title by Lisa Genova, “Still Alice” does not mean that Alice isn’t moving. “Still” in this case refers to the idea that throughout her decline, Alice remains the unique individual that she was prior to the disease taking its toll on her life. She is “still” a mother, “still” a friend, “still” a world-renowned professor, “still” able to contribute, “still” loved by her family and “still” valued.

Like the recent Robert Duvall movie “The Judge”, Still Alice forges into areas of loss and grief that are rarely depicted on the big screen. For those whose lives are dedicated to the compassionate care of those who suffer from dementia, these scenes are familiar. Unable to control their bodies, both of these films tackle what may be the final area of privacy left in our culture – incontinence. Tenderly addressing the embarrassment, anxiety and humiliation of incontinence, both movies share the power of respectful care at a time of incredible vulnerability.

It also tackles the difficult ethical issue of taking one’s own life to avoid the full extent of suffering. Alice advises herself (through a short movie) how to end her life once she can no longer remember basic elements of it. These scenes are heart-wrenching as the Alice who tries to end her life is no longer able to assess the implications of following the instructions she set out for herself. The movie does not set out to promote any viewpoint on this. Rather, it seeks to show the painful decisions and level of hopelessness that an individual suffers when living with this disease.

Still Alice moves an audience to enter into their own fears about their own possible diagnosis of dementia. It moves an audience to see the full breadth of the dementia experience. The viewer sees the loss, the grief and the hopelessness. We also walk alongside the family through a depth of support that transforms each individual touched by Alice’s progressive disease.

Still Alice is willing to tackle the tough issues of family dynamics – a husband whose day-to-day life must go on, a daughter who is faced with difficult genetic decisions for her children and another daughter who is reconciled to her mother through thoughtful, compassionate, initiating care. At one point, Alice tells her daughter that she knows they are fighting but can’t remember why. She asks if the daughter will forgive her so that they can move on. It’s an unexpected fresh start for the two of them.

Should you go to see Still Alice? The acting is authentic. The story is difficult. The heart is moved. If you are prepared to take an honest look at the journey of Alzheimer’s (more than you are already living), then you should go. Don’t forget to bring your kleenex. You’ll need it.

*Workforce Analysis, Health Sector Workforce Division, Ministry of health, Dementia (age 45+ years), March 24, 2004, Project 2014_010 PHC